Horse-heads and Spoken Shame: Níðstǫng and Cursing in Pre-Christian Germanic Heathenry

Cursing is as old as the need to punish, shame, or protect reputation within honour societies. In the corpus of Old Norse literature and law we find a family of practices clustered under the word níð: formalized shame, libel, and magical attack. The most visually arresting manifestation recorded in the sagas is the níðstǫng (often anglicized “nithing pole”): a pole topped with a skull or carcass and directed at a rival while runic or poetic words of shame were employed. But níð was not only visual spectacle... it included verbal libel, carved insults, rune-magic, and social sanction such as outlawry. Below I summarize what the sources show, how scholars interpret them, and how the practice sits within wider Old Norse ideas about honour, magic, and law.

What is níð, and why did it matter?

Níð in Old Norse denotes scorn, shame, libel... a form of social and spiritual attack that could strip a person of honour and social standing. To call someone a níðingr (a “nithing”) was among the severest condemnations available in Norse discourse: it implied moral corruption, cowardice, and social exclusion. The laws of medieval Scandinavia treat níð as serious: legal codes discuss verbal níð (tunguníð) versus carved or sculptural níð (tréníð), and some insults could force legal redress because reputation (and the right vengeance or compensation that flowed from it) was foundational to community order.

The níðstǫng in the sagas — the most famous examples

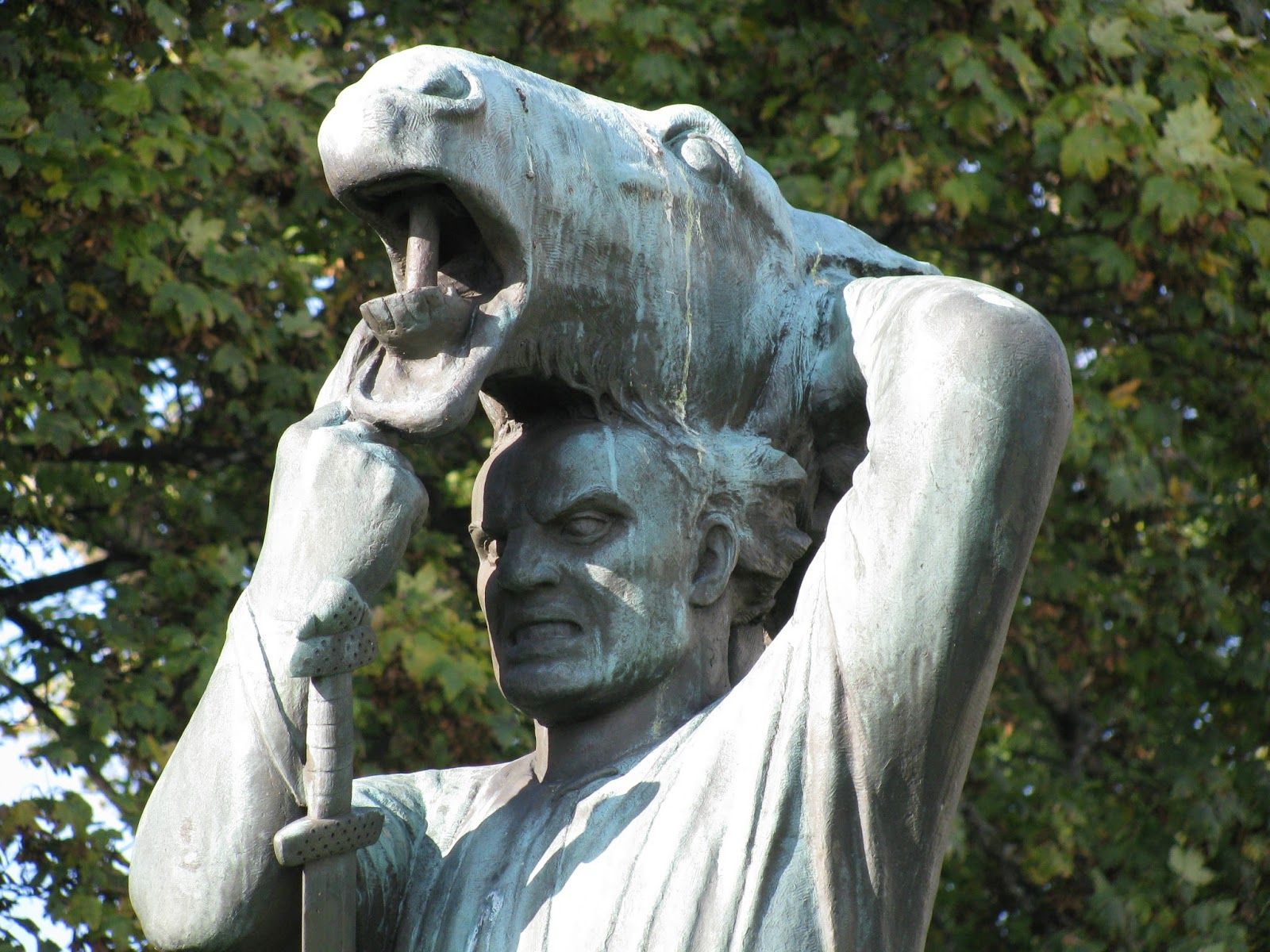

The most famous literary instance of a níðstǫng appears in Egils saga. The poem-warrior Egill Skallagrímsson, enraged at King Eiríkr and Queen Gunnhildr, takes a hazel-pole, fixes a horse’s head to it, carves runes and recites the formal words of the curse, then plants the pole facing the enemy’s land. The saga explicitly says Egill “cut runes, expressing the whole form of the curse.” This scene has become the canonical description used by scholars to illustrate what a níðstǫng looked like in narrative memory.

Other saga passages record variations: Vatnsdæla saga contains a similar, but more grotesque, account in which a carved human head appears on a post and animal entrails figure in the ritual; Gísla saga and other texts discuss carved poles or sculptures used to shame rivals - the literary corpus preserves both the ritual and the rhetoric.

How have scholars read the níðstǫng?

Scholars debate whether níðstǫngs were primarily magical (intended to do harm via ritual force) or performative (meant to publicly shame and pressure the target socially and legally). Rudolf Simek and others point out that while the horse’s skull and runes probably carried magical connotations, the appearance of carved faces and insulting gestures can also be read as a form of ritualised mockery... a “wood-shame” meant to mark someone as dishonourable in front of the community. In short: níð combined symbolic, performative, and (in the worldview of the sagas) effective magical elements.

Neil Price’s work on magic and ritual in the Viking Age helps contextualize níðstǫng within broader Norse practices (seiðr, galdr, rune-working) used to influence fate, heal, or harm... a suite of ritual technologies that could be wielded by poets, seers, and sorcerers. Price emphasizes that “magic” in the Viking world was embedded in social settings: reputation, patronage, and ritual authority determined whether a magical act was sanctioned or stigmatized.

Forms of níð beyond the pole

Níð is not reducible to the horse-head pole. The legal and literary sources distinguish several modalities:

- Tunguníð (verbal níð): libellous poems, scornful speeches, and insults - especially those implying cowardice, sexual deviance (labels like ergi), or being a sorcerer’s friend... were grave charges. Skaldic verse could function as a powerful social weapon when performed publicly.

- Tréníð (carved “wood-shame”): carved or sculpted images (effigies with grotesque features) placed where they would be seen by the victim’s community. The níðstǫng fits here.

- Runic inscriptions and galdr (spell-chants): runes could be inscribed to animate or fix an outcome; galdr (magical chant) could be used for both beneficial and harmful ends. These more esoteric forms sit at the intersection of poetry and magic. Neil Price and other scholars treat rune-work as part of the practical toolkit for influencing a person’s fate.

- Legal/social sanction (outlawry): to be declared an outlaw (útlegð) was effectively to be cursed by the community: loss of protection, exclusion, and the legitimisation of violence against the outlaw. In saga society, law and ritual shame sometimes worked in tandem.

The rhetorical content: what did níð say?

The substance of níð often targeted manliness, courage, and sexual reputation. Accusations of ergi (unmanliness or sexual passivity) were especially powerful because they attacked the social identity that bound a free man to rights and respect. Níð-stanzas (compact, sharp, and performative) could effectively “publish” someone’s shame; the literary record preserves examples where a single bite of verse drives conflict to bloodshed or legal action.

The horse’s head: symbolism and interpretation

Why a horse’s head? Scholars offer a range of interpretations. Some read the horse as sacrificial: a valuable animal given over to the ritual to animate the curse and enlist animal potency. Others suggest the gendering of the animal (a mare) could be an intended insult (implying cowardice or femininity), reinforcing the charge of ergi. Either way, in saga logic the horse-head is an unmistakable, visceral sign: an accusation posted where both land and community can “see” the shame.

Continuity and reinvention: níðstǫng in later and modern contexts

The níð-tradition did not die in the sagas. Icelandic newspapers record modern instances (2006, 2016, 2020, 2022) where poles topped with animal heads or other grotesqueries were erected as political protest or personal vendetta; such incidents have sometimes been treated as criminal threats rather than merely folk-protest. Atlas Obscura and Icelandic media have written accessible accounts of modern níðstǫng events, demonstrating how the symbolic grammar survives and can be repurposed... with all the legal and social complications that entails.

What can we responsibly conclude?

- Níð was social power. In a culture where honour, reputation, and public action governed rights and remedies, níð functioned as a potent weapon: it could shame, rally legal consequences, and—at least in literary imagination—reach into the metaphysical.

- The níðstǫng is both symbol and ritual. The pole is a dramatic, material form of níð that blends performance (public insult), visual rhetoric (a skull or carved head), runic communication, and perceived magical agency.

- Cursing practices sat inside a moral-legal framework. The same societies that recorded magical rites also maintained legal remedies and penalties; a níð could invite retribution or prosecution. The line between ritual insult and legal offense was porous.

- Modern echoes are complicated. Contemporary instances show how the imagery survives as protest, folklore, and threat; today such acts are judged through modern legal standards rather than saga logic.

Further reading / sources

Below are the main primary and secondary sources I used while researching this post... good starting places if you want to follow individual threads further.

Primary / saga texts

- Egils saga Skalla-Grímssonar — (English translations and online editions; ch. 57/60 contain the níðstǫng episode).

Reference works & scholarship

- Rudolf Simek, Dictionary of Northern Mythology — entry discussions of níð and the níðstǫng; helpful synthesis of sources and interpretations.

- Neil Price, The Viking Way: Religion and War in Late Iron Age Scandinavia — major modern treatment of magic, seiðr, and ritual practice in Viking/Norse contexts.

Articles, legal background, and analyses

- “Níð, ergi and Old Norse moral attitudes” (scholarly treatments and PDFs discussing tunguníð and tréníð).

- Studies on Grágás and medieval Icelandic law (background on outlawry and legal implications of slander).

Contextual & popular sources (examples, modern cases)

- Atlas Obscura — “The Return of Iceland’s Nithing Poles, or Dead Horse …” (overview of saga account and modern instances).

- Iceland Review and contemporary press reports documenting recent níðstǫng incidents (examples of continuity and legal response).