The Idisi: Women of Fate, Battle and Blessing in Germanic Myth

The Old Germanic word idis (OHG itis, Old Saxon idis, Old English ides) generally means “woman,” often with connotations of dignity or status: a matron, respected woman or noble lady. But in the fragments of continental and insular Germanic evidence that survive, Idisi sometimes appear as more than human: they behave like semi-divine female beings who bind, loose, protect, choose or afflict at key moments in war and fate. These patchy but fascinating traces make the Idisi a liminal and polyvalent class of female powers in the Germanic imagination. Let's get into it...

The clearest surviving witness: the First Merseburg Charm

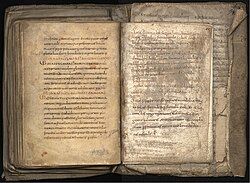

Our single most direct continental testimony for the Idisi is the First Merseburg Charm, an Old High German incantation preserved in a 10th-century manuscript from Merseburg. The charm contains a short mythic preamble and a command formula. The preamble names a group of “Idisi” who sit “here and there,” some fastening fetters, some hampering the army, and some loosing the bonds... after which the spell orders fetters to leap and prisoners to escape. That brief passage is the most concrete evidence we have that a Germanic conception of supernatural women who could bind or unbind forces on the battlefield once circulated in the Germanic world.

Eiris sazun idisi,

sazun hera duoder;

suma hapt heptidun,

suma heri lezidun,

suma clubodun

umbi cuoniouuidi:

insprinc haptbandun,

inuar uigandun

Why is this important? Because the verbs and imagery (binding fetters, hampering an army, unloosing bonds) are precisely the sort of powers that later sources attribute to related female beings (valkyries, dísir, norns): to determine outcomes in battle, to protect or punish, and to intervene in fate. The charm thus places the Idisi in a functional neighborhood that overlaps with other female entities of Germanic lore.

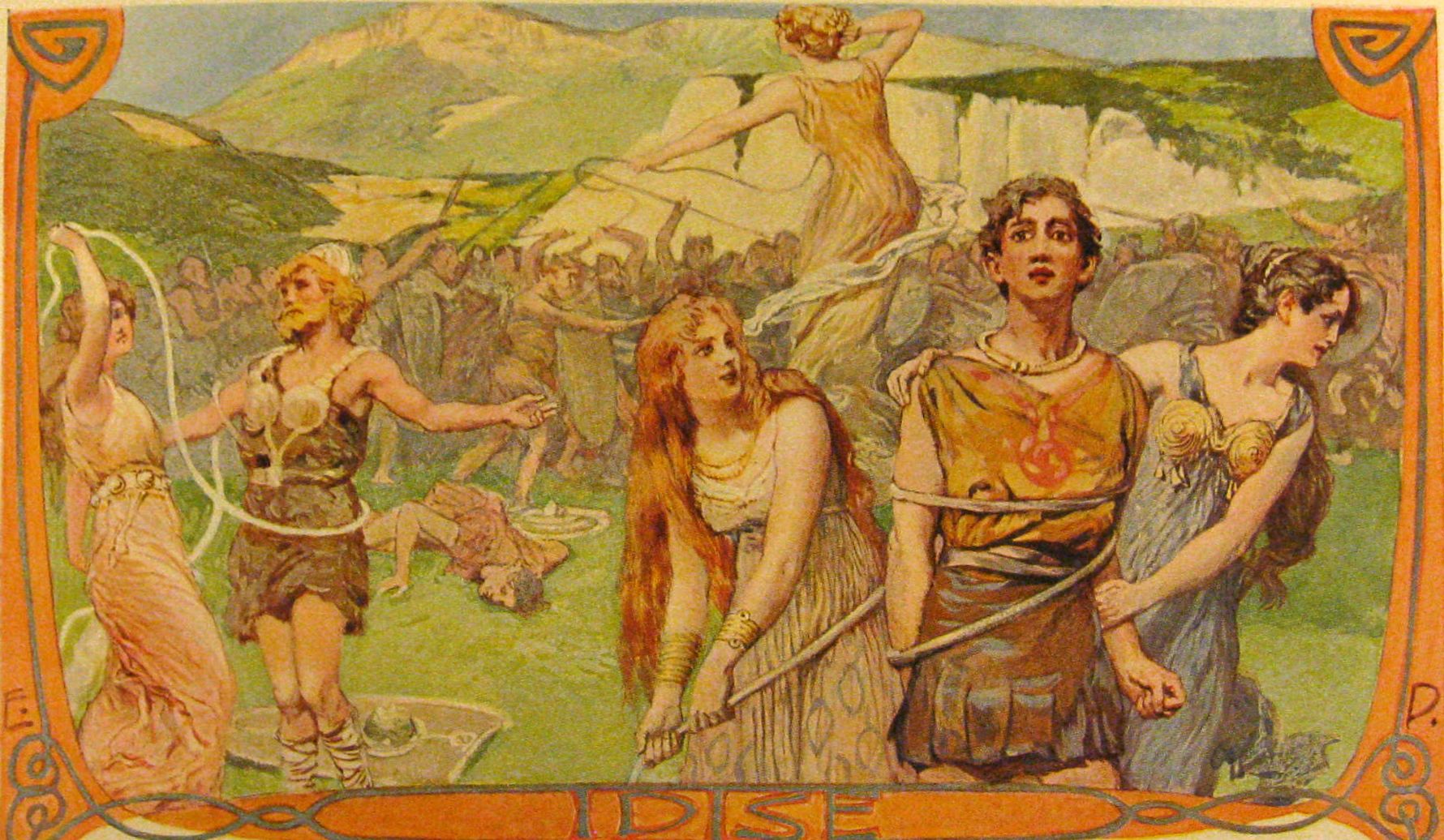

Idisi, Dísir, Valkyries: same family, different facts

Scholars typically treat Idisi as cognate with the Old Norse dísir (and by extension related to the Old Norse term dís and to Old English ides). The semantic range is broad: in some contexts the term simply denotes any lady; in others it points to supernatural female beings with roles that can include guardian spirits, ancestral matrons, fate-givers (norn-like figures) or war-choosers (valkyrie-like figures). Rudolf Simek, Hilda Ellis Davidson and others argue that the Idisi named in the Merseburg charm are likely a kind of valkyrie-like figure because of their explicit power to hamper or free warriors... a classic valkyrie function in Norse sources. Still, not every idis in the sources is a valkyrie; the term’s use is context-dependent.

Two points help to keep the picture tidy:

- Linguistically, idis/itis/ides across Germanic languages often marks a “dignified” woman (the same root that gives the Old English courtly word ides).

- Functionally, when Idisi are invoked in magic or myth (as in the Merseburg charm), they behave like supernatural female agents who can influence warfare and fate: behavior also found in the corpus of valkyrie and dísir lore.

Place-names and classical references: traces beyond the charm

The name Idisiaviso (interpreted as “plain of the Idisi”) appears in classical Roman reports of Germanic geography and warfare (Tacitus and later sources report a location tied to clashes between Roman forces and Germanic tribes). Place-names like this and brief external references hint that the concept of the Idisi (or at least of sacred female collectives) was visible enough in the early centuries CE to be encoded in landscape and to be noticed by external observers. That adds weight to the idea that Idisi were once part of more widespread religious or folk practice.

Functions and imagery: what did the Idisi actually do?

From the available sources we can list several recurring functions:

- Bind and unbind: The Merseburg charm is explicit that Idisi could fasten fetters, hinder an army, or loose fetters... a literal magical control of constraint and freedom. This is one of the most striking and tangible “powers” ascribed to them.

- Choose and escort the slain (valkyrie overlap): Because their actions influence armies and individual warriors, later scholars situate the Idisi near valkyries in role if not always in name. They may choose who is hampered, who is protected, or even who dies.

- Guardian / ancestral / fate roles (dísir / norn overlap): In Icelandic tradition and some continental echoes, the dísir could be ancestral guardians or fate-related female powers: suggesting Idisi could similarly function as household or clan protectors, or as fate-weavers in certain contexts.

Because the surviving evidence is fragmentary, the Idisi’s roles should be understood as overlapping categories rather than tidy modern taxonomies.

Scholarly debate and cautions

A few caveats scholars always stress:

- Limited data: The Merseburg spells and a handful of Old English poetic usages (e.g., ides in Beowulf to denote noble women) are the core evidence. That’s not enough to reconstruct a full cult or theology. Interpretations must therefore be cautious and comparative, drawing on cognate Norse evidence to fill gaps.

- Polysemy of the term: Because idis is both an ordinary word for “lady” and a possible technical name for supernatural women, one must carefully interpret each occurrence in context rather than assume a uniform supernatural class wherever the word appears.

- Cross-cultural projection: Using richly documented Old Norse material (Eddic poems, sagas) to interpret continental Old High German fragments is common and useful, but it risks projecting later Scandinavian mythic developments back onto sparser continental evidence. Scholarly work tends to balance Scandinavian riches against continental caution.

The Idisi in modern practice and imagination

In contemporary heathen and reconstructionist contexts the Idisi are often revived as a matrix of ancestral, protective and warrior-feminine powers. Some groups invoke the Idisi in rites of protection or at liminal moments (battles of the spirit, threshold crossings); others study the Merseburg charm as a model for how ritual language might be constructed. If you choose to work with the Idisi in ritual, keep the historical humility: the sources show function and attestation, but they don’t give us a full liturgy or theology...there’s respectful room for creative reconstruction anchored to the texts.

Final Thoughts

The Idisi sit at a crossroads in Germanic religious imagination: linguistically ordinary women and mythically potent female beings overlap in the surviving record. The Merseburg charm remains our sharpest window: a few lines that preserve a living sense of women who reached into battle and fate itself to bind or loosen the world. That small window has helped modern scholars link Idisi, Dísir, Valkyries and Norns into a looser family of female powers... and that network continues to fascinate practitioners and scholars alike.

Sources / Suggested Reading:

- Rudolf Simek, Dictionary of Northern Mythology (1993 / rev. ed.).

- H. R. Ellis Davidson, Gods and Myths of Northern Europe (1964).

- Jacob Grimm, Teutonic Mythology (classic reference; 19th century).

- Wolfgang Beck, Die Merseburger Zaubersprüche (ed.), and modern translations/commentaries by Joseph S. Hopkins (Hyldyr Press) and others.

- John Lindow, Introduction to the Merseburg Spells (online essay / commentary).

- Merseburg Cathedral / Domstiftsbibliothek page on the Merseburg charms (manuscript display / context).